Visceral Control

One of the pleasures and horrors of modernity is the control of something larger and more powerful for our ends. That you can do so much more, and then hold on for dear life. Motorcycles are like this. Flooring the accelerator on a Tesla is definitely like this. Weirdly bikes aren’t quite the same — maybe because they’re multipliers of one's own power instead of pulling power from another source?

Taking control of these power sources is usually a somewhat extreme learning process. I didn’t learn how to drive until my late 20s (and only did thanks to my extremely patient wife, since I learned on our stick shift VW) — and when I did, the process was literally halting. Developing a feeling for the clutch, understanding when to shift, and learning how to recover from a stall. All of these things stood in the way of me expressing a goal through this object that otherwise was quite powerful but constrained by my own ability to control it.

But that changed. Before long, I’d learned to shift through the audible and haptic feedback that the car was giving me. I figured out that pressing the gas wasn’t just power up/power down, but rather something that was invoking or manipulating an existing process. Stepping on the gas wasn’t linear, but rather a coaxing of resources towards some end. This shift in the mental model around control ended up making the whole experience of driving that much more enjoyable and natural. In the same way that an experienced cyclist orients their bike as an extension of their body, controlling a vehicle that wasn’t powered by me became a matter of orchestrating different signals harmoniously. Strangely though, this experience has left me uncomfortable driving automatic or electric cars.

Writing about peripherals last week, there’s a more specific piece around simulation that I think is worth exploring. The first is simulation and to what extent our control interfaces take us in or out of our experiences (and how important is that actually?). The second is immersive visuals through VR, and why that type of immersion might not be the immersion that we think it is. And finally the third is how to feed simulation back into the real world — basically whether or not we can use simulation effectively to prototype alternative realities. The thing I think I want to talk about today is the first one.

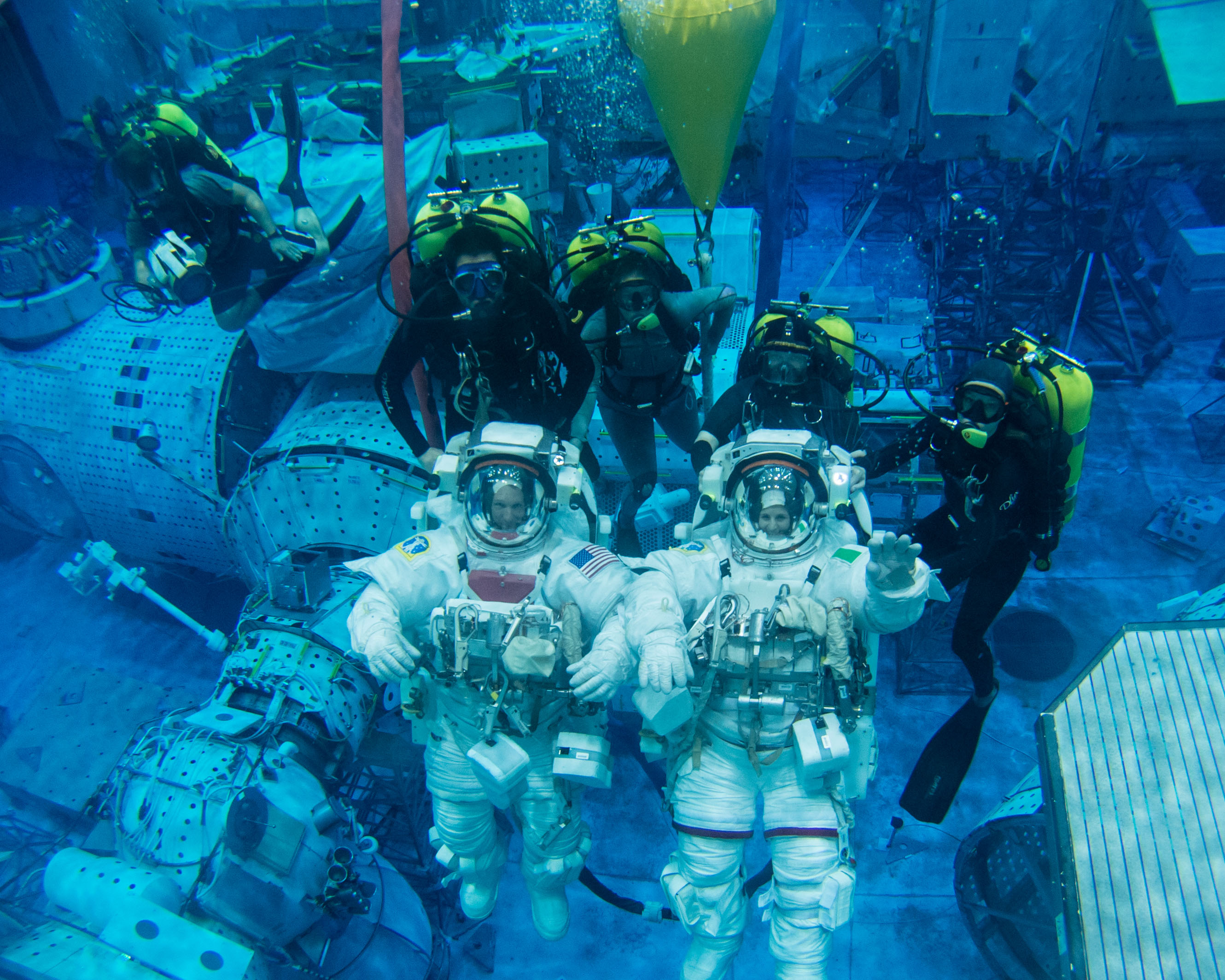

There’s a lot of different kinds of simulation — with “training for real things” level that you see in a defence context, to “We’ve simplified this so you buy in, but it's nowhere near the real thing” type of arcade experiences. In-between, you get an entire gamut. Defense Combat Simulator is on the upper end towards defence level simulation, Ace Combat 7 is on the low end towards arcade simulation. Then (and we won’t dig into this too much, but it’s worth mentioning), you have non-digital simulation experiences that get one “most of the way there.” One might think of astronauts floating in pools:

Or US Navy pilots going through G-force training (also wtf):

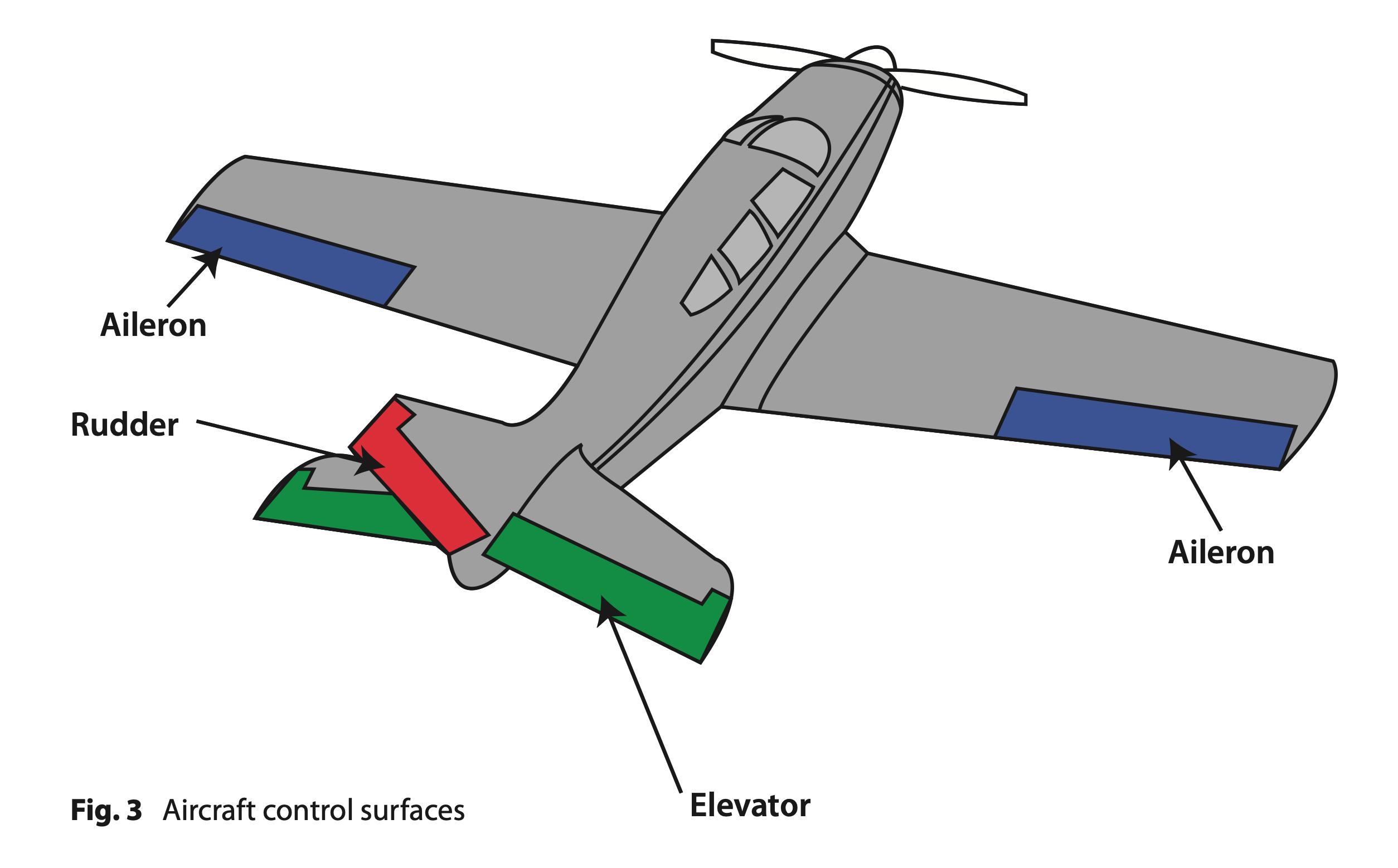

These kinds of simulations are all oriented around real experiences. Air Combat 7 (a weird but fun game) just sticks us in a plane and has us fly different missions — the “realism” is purely around the most basic pitch, yaw, rudder, etc. controls that one sends to the plane itself. DCS puts us in control of a pretty accurately modelled fighter plane, and you need to figure out how to turn on the radio inside the cockpit itself.

On the arcade end of the spectrum, this feels a bit like driving an automatic car. The connection to the object of control is simplified to the point of feeling almost tangential. The plane-shaped avatar in the game continues on fine without us, we just happen to direct it one way or the other — and it figures out the rest. On the “close to real but not quite” end of the spectrum, it’s the opposite: one has to close the cockpit yourself, enable wheel steering, and know enough about the dynamics of flight to land the damn thing at all — much less land it with skill. That 10% difference then becomes the “shortcuts” built in to make things a better “we know this is a game” type of user experience — quick starts, default settings, the ability to respawn.

The problem is you can’t really do the “close to real” end of the spectrum with our standard peripherals. A mouse has two axes of control we call X and Y, which we use to control a cursor on a flat plane. Conversely, a plane has multiple axes of control: Pitch (elevator, or the Y axis of the stick ), roll (ailerons, or the X axis of the stick), and yaw (rudder, which needs something like a twist stick or actual pedals to control). Then you get into issues of controlling trust, etc. And then each of those axes isn’t just on or off —but rather needs to be represented across a wide set of numbers between its minimum and maximum extensions.

You can’t do this effectively on a computer without the actual peripherals of control — the joystick, the rudder, the throttle. etc. Far from just breaking the sense of immersion, what you end up simulating if you try to control that is not an experience, but just the flight model itself: what does the plane do given these conditions? We can, in theory anyway, simulate that 99.9999whatever% in the computer. But with a VR headset, a HOTAS (hands-on throttle and stick), and a rudder set up, I suddenly have multiple axes of control: 2 via joystick, 1 via throttle, 1 via rudder, and at least 3 via the VR headset tracking. Which still only takes us 80, 90% of the way there.

I don’t think that’s a problem.

What’s interesting is that when we start to break these layers of control and experience down, it gives us some interesting insight into what we might design given these increasingly common peripherals. Let’s say I wanted to control a pick-and-place style robot remotely from my computer. I could set up that control via keyboard, and so each press is a binary ON or OFF. I can then map those on and off signals to the robots and say “A means LEFT. When LEFT is ON move gantry LEFT.” This would result in jerking movement that would require incredibly fine timing to get me to a precise point on the robot’s X/Y axis. If you’ve ever controlled a crane machine at the zoo with buttons, this will be a familiar feeling.

What if I had a trackball set up? The trackball gives me two axes of control, but those axes of control are determined by velocity. I spin the trackball in different directions and the velocity of that movement is translated into control signals. In this scenario, I might be able to control the gantry incredibly effectively — looping it towards its target quickly before slowing it to a more precise stop. It’s almost like spinning a globe and settling on the spot that you aspire to go.

Or, I could use a mouse: it also gives me two axes of control, but that control is maybe ill-suited to this station. We’re trying to position a gantry at a precise X/Y coordinate, but then, that coordinate is angled away from us. When we use a mouse on a screen, coordinate plane we’re traversing is in a kind of “top-down” position, so it's relatively easy for us to situate it on that plane. Conversely, imagine trying to use a mouse to click on a window if you were looking UP at the monitor. The least reliable thing in Jurassic Park is that Lex found anything on this filesystem using a mouse.

Or, of course, you could use a joystick. Two axes of control with specific “pressure.” So while the trackball exerts “pressure” via the velocity of its spin, the joystick is used to exert pressure via the degree of movement along the axis. A slight forward hold means the gantry might move slowly and precisely, a full push provides crude but quick movement.

Part of the fascination with interfaces like this is where certain dogmas have come into play. Take the car steering wheel: The fact that you TWIST something is an outcome of a mechanical reality like the steering column and the previous lack of tools like power steering. The steering wheel reflects our physical reality as much as the car’s physical reality. It’s also probably why such cars can be more fun to drive than fully automated ones: there is more of a synthesis between our bodies and the machines we control.

But lacking that need, how else might a car be controlled such that it's appropriate to the task and visceral in the experience of that control?

One of my personal vices and “fandoms” is the Gundam series, which I was introduced to as a kid and have frankly never really grown out of (I tried and relapsed). And one of the things that have always been interesting about it, is how the control surfaces are constantly reinvented over the years as people try to bridge the conceptual gap between “hard” science fiction (i.e. this could actually happen) and the sci-fi fantasy surrounding what are basically anthropomorphized tanks. It’s a non-stop source of inspiration, frankly. Chris Noessel wrote a very good book on it and runs a blog about it, and you’ll find tons of other blogs trying to think through it, like this one.

It all comes down to a pretty interesting question though: what’s the interaction design of a fantasy? If a mobile suit from the Gundam series can move like a plane but manipulate like a person, what does that interface between our intentions and such a capability look like?

Anyway, I’m going to just leave that here for now since this is getting a bit long. Next, I’ll be looking at considerations around immersive visuals, and then that topic of feeding simulation (however fanciful) back into the real world and real work.