Legibility in Work and Fiction

My path to technology and design is rooted in fiction. I realized this by when I revisited the source material. Here's a little note about Cryptonomicon, being legible, and startups.

Cryptonomicon

I listened the the audio version of one of my favourite books — Cryptonomicon by Neal Stephenson. This book has always been fun for me, but I don't think I had entirely acknowledged its influence on how I think of the startup world on a normative level.

Basically, Cryptonomicon is an "social science fiction" adventure across two paralleled storylines — one in the late 90s dot com startup economy with a team of startup-types (explicitly using the metaphor of the Tolkien fellowship at times); and one taking place during World War 2. The main characters in both time-periods are mostly character archetypes and family lines from Neal Stephenson's older series, the Baroque Cycle — Shaftoe the vagabond, Waterhouse the engineer/mathematician, Comstock the dilettante, etc. We get a wonderful treatments of historical characters like Alan Turing and Douglas McArthur in there as well.

In the World War 2 timeline, the characters live are overcome with how critical their skills with technology or cleverness relative to the war effort — and they lack a certain agency in applying these skills. The work is focused on cryptography, and the creation of the digital computer. Eventually however, they gain agency through accumulating power, or resources, or knowledge — and the importance of the war takes a back seat to their own interest, relationships, and beliefs.

In the dot com era timeline, there's an inverse at play. The characters start with agency and lack focus. They exist in the era of computers, and specifically software and networks. They start with experience, community, and some resources developed almost by mistake — but because their environment doesn't give them purpose, the main character in particular finds himself (using the Tolkien metaphor) "stuck in the shire." This changes when the team creates a startup, and over the course of a year pivots their way around south-east Asia in the name of pursuing 'shareholder value' while having a bunch of adventures — culminating in each finding that overriding purpose and something new being created.

There's a LOT more to the book than that (the information theory part itself is so, so well done), but for the purposes of this post, the thing to take from it is the adventure. The storylines orbit around the "new" in technological terms — the computer and the internet. And within that orbit, the characters are drawn into opportunity, danger, discovery, and awareness which results in an incredibly satisfying conclusion.

What was so incredibly striking for me as I immersed myself in this story again, was this thought "well shit, this is where my idea of starting a company comes from."

Shareholder Value

I've had a few forays into the startup world, but have never entirely committed.

- I created and ran Knowsi, a bootstrapped SaaS product which was semi-profitable — but it was part time, explicitly didn't have external investors (though Sage Publishing provided a grant and network), and the idea wasn't "big." From the start, I wanted the idea to be small because I thought of Knowsi as one part of a portfolio of products I would pursue.

- I've worked at three startups at different stages: pre-product as a founding IC, late-stage scaleup, and actually my first real employment experience was a highly volatile academic spinout. Usually in a design, research, and prototyping capacity.

- I've consulted with startups in a few different ways: early product discovery and prototyping; strategic sparring with the founders; and capacity building.

- I designed and supported a training curriculum for a startup accelerator

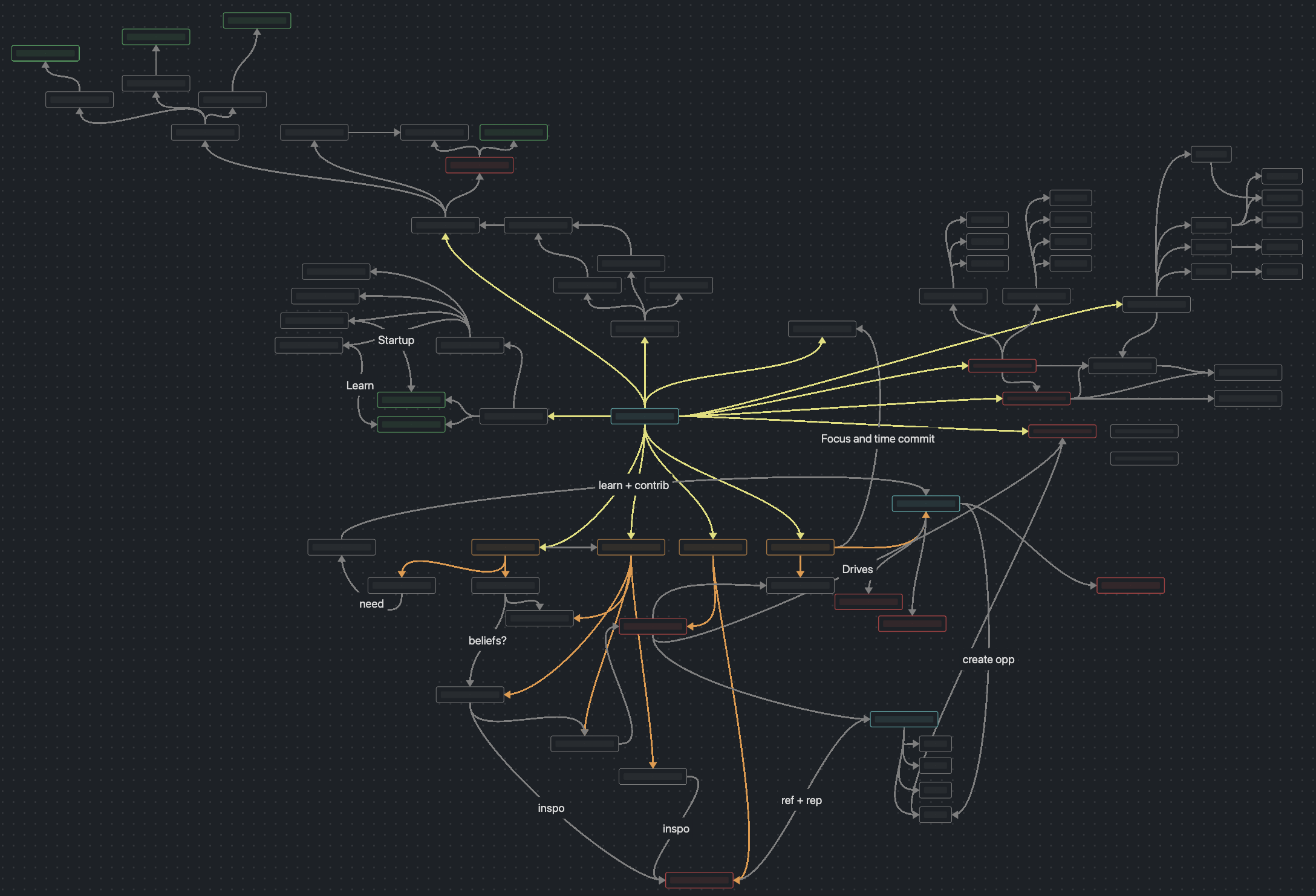

I have been trying to "make sense" of these experiences recently to focus in on my own summer strategy, and after an exhaustive multi-hour session with Obsidian canvas, this map emerged.

Now, I would love to share in more detail, but there's a set of client references that can't leave the encrypted vault. But a few trends emerged:

- Moving to Denmark and becoming a parent has dramatically changed my frame on "good work", especially relative to novelty-seeking.

- My inner world of writing, building, and sharing is MORE intertwined with the social and family than my paid work is — especially when working as an individual contributor.

- I've created unconscious barriers between personal life and work life that I don't think serve doing good work for reason's I'll go into.

- These barriers between personal work and commercial work meant that interest and expertise become less externally legible because the question of "wtf does Andrew do?" becomes hard to parse depending on where you look at my work.

Basically, a core thing I've taken away from this process is a need to think a bit more critically around how community and work intertwine. In Cryptonomicon, the community came about in two ways:

- Hierarchical: In Cryptonomicon's WW2, people were thrown together through a greater strategic will (gov, bureaucracy, etc). Those individuals then organized within and around that will, creating within constraints.

- Distributed: In dot com era, people accreted around technology and defined a tribe; and then that tribe dispersed and did interesting things. They would then come back together around affinity and capital; creating around opportunity.

Working in a consulting fashion forces you to be a bit of a semaphore on this front: flipping back and forth between identifying opportunities and the skills around them — and then turning that into something useful for your client. Opportunity, constraint, opportunity, constraint. The key here is that being legible is what empowers you to do good work in either systems.

Huff Duff

Unfortunately legibility is forever incomplete and asymmetric. Cryptonomicon uses the idea of the "Huff Duff" station to communicate an information asymmetry: Huff Duff Stations were used to identify the location of a transmitting U-Boat. The Huff Duff operator swings their station in decreasing arcs to narrow in on what direction the U-boat is transmitting from — and dispatch a Catalina to find and sink it.

The Huff Duff station is situated in spots that might be advantageous to spot subs (eg. an isthmus or an island) — but share only limited dimensions of the target: direction and time (and noisy amplitude). Multiple stations can coordinate to triangulate on a signal, but that requires some degree of communication — networked or centralized.

The U-boat has the opposite problem: it knows that someone might be listening and that transmitting incurs risk. But the upside of that risk is high. It doesn't know HOW ambient observers might observe or sense it — only the risk that it might be.

Anything outward we do can pollute the legibility of your skillset to those trying to make sense of your work. Think of potential collaborators or clients as huff-duff stations: you pop up briefly via a project, a post, or a referral. Your work is interpreted from their particular position, and that's it. If you're lucky and multiple individuals within a network are communicating, they might triangulate on a more representative and accurate idea of what it is that you do. Alternatively, if you pop up multiple times, then that one observer can get a more accurate view of that one angle. Either way we want to do the opposite of the U-Boat — maximizing the opportunities for others to observe — when, like the U-Boat, we don't know anything about the configuration and location of our observers.

This can present great opportunities if you're a specialist: you pop up around a specific skill and specific trajectory, and that one station can observe that trajectory as you go. If you're a generalist, it becomes much more important for you to be observed by a network so that they can triangulate in on a pattern of creation.

Catalina

In a way, building Knowsi as an indie designer/dev/product person backfired a bit on me.

I had set out to use it as an example of end-to-end product creation — but accidentally became known as a user researcher for a lot of consulting opportunities after that. To market Knowsi, I was popping up a lot to do research subject matter: whether it was webinars, writing, or speaking. I love doing the work of researcher, but it's a hell of a lot nicer when you get to make something out of it after that phase is wrapped. So it's reasonable the professional huff duffs focused on that trajectory.

I think an alternative strategy is to focus on popping up in places were a network is more likely to exist. We want to be triangulated upon by a network that is sharing both purpose and information, so that the network can observe our skillsets and contributions more readily. Speaking at a local conference does this because people are talking about your work afterwards. Writing can do this, because folk can respond, share, or critique your arguments. Creating sharable projects either out of novelty or as an open source utility can do this. All of these mediums encourage the distributed affinity-based network to triangulate their observations around your work and — maybe — give rise to an opportunity.

This isn't useful if the network isn't oriented around triangulation or synthesis. Linkedin is a noise-scape for this because triangulation isn't occurring despite the presence of a network: instead it's like each observer uses an observed transmission to transmit their own location. I'm still trying to sort out what I think about this re: other short form social media (eg. my instagram experiment), but from what I've seen so far, it's closer to the solitary huff duff station observing a series of transmissions over time.

Golgatha

So returning to startups and adventure: last week some friends asked me why the hell I didn't take a stab at a venture-backed startup. I have plenty of practical reasons (IMO most companies shouldn't be VC, I distrust pre-product funding, etc), but the biggest one is that I don't think I've created a context in recent years where I'm properly able to observe and triangulate on the work of others — nor make myself legible to them. And that is something I should change. After all, what I want from my career is to use my skills and experience to explore, expand, and discover — to have an adventure that can be life-long. And those adventures come when opportunity does.

Revisiting Cryptonomicon's depiction of "the startup" has helped frame that up for me. Consulting is actually doing a lot to reinforce the "adventure" side of things (a safari for systems thinkers), but when it comes to making something new, there are two quotes that I made a note of that I'll end with:

“That would be expensive.”

Eberhard waves his hand dismissively.

“Bandwidth is cheap.”

“That is more an article of faith than a statement of fact,” Randy says, “but it might be true in the future.”

“But the rest of our lives will happen in the future, Randy, so we might as well get with the program now.”

Stephenson, Neal. Cryptonomicon (p. 283). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

and this one, which hits a bit different re-reading it as a parent:

So he picks up the boy and carries him through the compound, down semicollapsed hallways and over settling rubble-heaps and between dead Nipponese boys to that big staircase, and shows him the giant slabs of granite, tells how they were laid, one on top of the next, year by year, as the galleons full of silver came from Acapulco. Doug M. Shaftoe has been playing with blocks, so he zeroes in on the basic concept right away. Dad carries son up and down the stairway a few times. They stand at the bottom and lok up at it. The block analogy has struck deep. Without any prompting, Doug M. raises both arms over his head and hollers “Soooo big” and the sound echoes up and down the stairs. Bobby wants to explain to the boy that this is how it’s done, you pile one thing on top of the next and you keep it up and keep it up—sometimes the galleon sinks in a typhoon, you don’t get your slab of granite that year—but you stick with it and eventually you end up with something sooo big.

He wishes that he could also make some further point about Glory and how she’s been hard at work building her own staircase. Maybe if he was a word man like Enoch Root he would be able to explain. But he knows that this is going way over the toddler’s head, just as it went over Bobby’s head when Glory first showed him the steps. The only thing that’ll stick with Douglas MacArthur Shaftoe is the memory that his father brought him here and carried him up and down the staircase, and if he lives long enough and thinks hard enough maybe he’ll come to understand it too, the way Bobby does. That is a good enough start.

Stephenson, Neal. Cryptonomicon (pp. 774-775). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.