Diverge Weekly Issue 13 The Endemic Issue

As the exogenous force of coronavirus has pummeled the globe, America has had its own endemic disease roar to the surface.

On February 23rd, Ahmaud Arbery was chased down while he was on a jog by vigilantes in Georgia and murdered in a terrifyingly modern lynching. Because they are white, because Ahmaud was black, and because Georgia remains a bastion of white supremacy in the United States, Ahmaud’s murderers were initially released and uncharged. It was only after the video became public that any form of criminal proceedings started 74 days after his murder, on May 7th.

On March 13th, Breonna Taylor, an EMT in Kentucky, was shot eight times in her home after police entered on a “no-knock” warrant. As the police did not identify themselves, Breonna’s boyfriend Kenneth Walker thought they were experiencing a home invasion and attempted to defend himself and Breonna. Gun ownership is widespread and legalized in the US, and Kenneth fired at the legs of one of the officers, not knowing it was the police. Breonna Taylor was killed by indiscriminate return fire. Kenneth’s call to emergency services stated “I don’t know what happened … somebody kicked in the door and shot my girlfriend.” Shortly after, he was arrested by the police for assault. The individual the police were searching for was already in police custody when the police invaded Taylor and Walker’s home.

On May 25th, a video surfaced of Christopher Cooper, a New York City birder, being verbally attacked by Amy Cooper (no relation) in Central Park. Christopher was birding, and Amy was walking her dog without a leash in a section of the park that requires leashing. When Christopher asked her to restrain her dog, Amy called the police on Christopher and specifically identified him as “African American” in an attempt to express her understanding of power over him as a white woman living in a society founded on white supremacy. Amy’s actions resulted in her losing her dog and her job, as well as her being brigaded online. But in a time before smartphones and online video, Christopher might have lost his life and certainly would have lost his dignity, his freedom, and his security.

Finally, on the same day in Minneapolis, a white police officer had his knee on the neck of George Floyd — choking him to death over the accused use of a counterfeit $20 bill and George’s justified fear of the men who had taken him into custody. The police officer’s knee didn’t move for eight minutes and forty-six seconds as George begged for his life, lost consciousness, and died.

In the week since George Floyd was murdered, protests have started and escalated across the United States and around the world. For example, in Copenhagen, 2000 people marched on Sunday in front of the US embassy, a sign of support and outrage against a system that the United States has —unfortunately — come to stand for: white supremacy.

I write a lot about systems in this newsletter, and how systems come to be influenced, leveraged, and undermined. I believe that the real intersection between design, politics, and international relations is around this capacity to not DESIGN systems (which is hubristic and insane), but rather influence and navigate systems (which we can do both intuitively and intentionally). Trevor Noah articulated the flashpoint of the past month brilliantly, starting with Amy Cooper. “You have this woman who blatantly knew how to use the power of her whiteness to threaten the life of another man and his blackness.”.

Amy Cooper was intuitively leveraging a system of power that is endemic to the United States. Because of the circumstance of her birth, her geography, her genetics, and the history of the country she inhabited; she occupied a space where she could exercise power. Given her acculturation and lack of critical engagement, she understood how she could use that privilege to get what she wanted.

In Isabel Wilkerson’s book The Warmth of Other Suns on the migration of black Americans away from the South between the 1920s and the 1970s, she describes the violence that black Americans faced and that was utterly normalized in that society. Speaking of the period following World War 1, she states “All blacks lived with the reality that no black individual was completely safe from lynching.”

This is the reality of American society that many have tried — in different ways — to heal, to cure, to expunge. The election and widespread popularity of a black American president, the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, abolishing the 13th amendment and banning slavery. These are all incredible and laudable steps, but are they just treatments for something that lies at the very center of American society? Something that is endemic? What I’ve learned and come to believe over the years is that perhaps this can’t be cured or treated in isolation — instead, that the problem cuts across the whole system.

Currently, in America, people are on the streets questioning the very foundation of that system and whether it is actually worth saving. The far-left wing of the Democratic Party is asking the same thing — is it time to completely remake the system? Overwhelmingly the protests have been peaceful (which is the ideal and according to scholars like Erica Chenoweth, ultimately a hell of a lot more successful), but I think it’s also important to acknowledge the legitimacy, the rage, the fear, and the trauma that spurs more violent forms of protest and property damage. The razing of a police station after the police murdered an innocent man can be argued as proportional — property can be rebuilt as funded by taxpayers, but a life stolen is lost forever.

Systems of power and oppression are often parasitic to something more fundamental: powerful actors within those dominating systems irrevocably wrap themselves in the flag, for example. They will insist that to question it is to question other values, peoples, and histories. But it’s more complicated than that. America should be proud of its role in crushing fascism and the Nazis in World War II, while also being ashamed that black American soldiers were lynched for walking with pride upon returning home from the war. Systemic ideals like checks and balances between the governing houses and the rule of law can be lauded for their intention, even if the result included the perpetuation of Jim Crow laws in the South for most of the 20th century, and a de facto or new Jim Crow system through mass incarceration of black Americans.

Anyway. Something has to change. America as a concept and as a country will not collapse if state and local police are held to a higher account. It is not unpatriotic to do everything in your power to destroy the gerrymandered voting system that perpetuates white supremacy in elected offices and violence against black Americans in their policies. And it is absolutely reasonable to insist that black lives matter more than the property, prosperity, and power built through the centuries-long perpetuation and continuous reinvention of a racist caste system.

Security Blanket

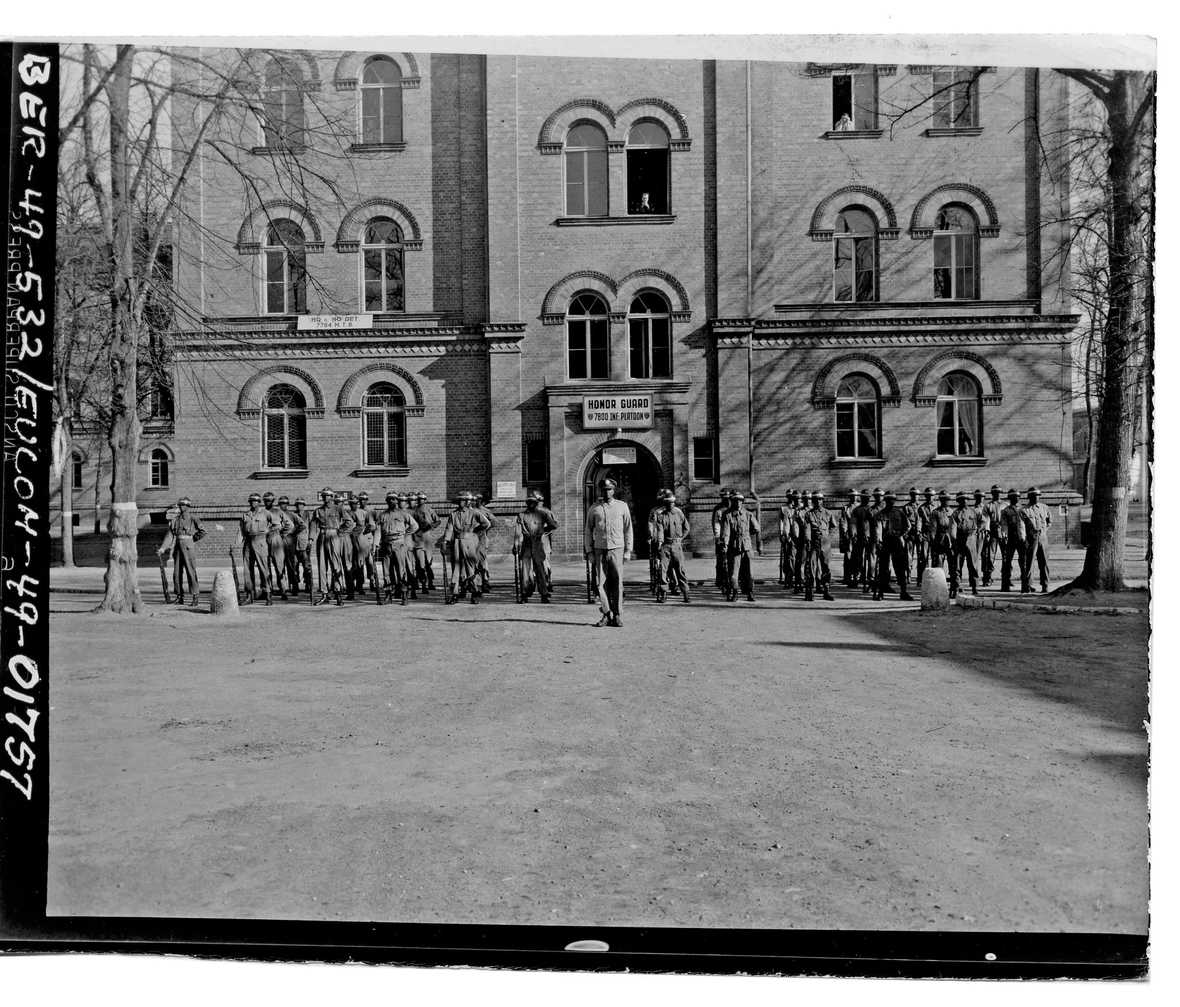

When Jim Crow Reigned Amid the Rubble of Nazi Germany

I got curious about this while reading of Robert Joseph Pershing Foster’s military service in Germany before and after World War II in The Warmth of Other Suns. His experience sounded like something that was all too common, and unfortunately, it was. This article does a good job of reviewing the contribution of black Americans in the war against fascism, and the reality that many white American soldiers brought the norms and expectations of a Jim Crow America with them in their dealings with their fellow soldiers.

It’s worth giving this article a read. I didn’t know a fair bit of this history, and while much of it wasn’t surprising, some of the ways that race and class played into cold war posturing was quite new. Finally, I found this quote summed things up effectively:

“Despite their treatment by white American service members, a number of black troops expressed their preference for life in Germany compared with back home. The percentage of black G.I.s extending their tours of duty in Germany was three times that of white G.I.s.”