Bureaucratic Mysteries

These tools were taught as a workshop to the first Code for Canada fellowship *team in November 2017. Article originally published in Medium*.

Building the actual product or technology is rarely the coda on the work that is social entrepreneurship and government software. More frequently, we see much of the labour existing in collaboration with our government and civil society partners: in building consensus, forming coalitions, cutting through roadblocks, and mapping the bureaucracy.

In my time at the US Digital Service, IDEO, and more recently New America, there are a set of tools I often apply in working through this complexity and communicating that complexity with my team. And a significant part of this technique I believe comes from some mental muscles I developed in college studying classical literature. In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the characters create a densely interconnected — but logical– community of influence. Zeus sits as king: impertinent, meddling, and cruel. Hera is at his side, manipulative, jealous, but loyal. Athena is the goddess of wisdom and all things military: untouchable, disciplined, and wise. Hercules is the human face of divinity: brash, contradictory, and flawed.

Each of the gods in the Pantheon represented a place in Greek cultural thought. They are metaphors through which people described the world, and rationalized what they observed in it. In doing our work as government technologists, we daily encounter the same mythologies. Bureaucracy ebbs and flows in its daily patterns, but when the dam bursts or the crops die, we scramble for explanations as to why.

The goal of these tools is to untangle the web of stakeholders that make up any given technology project and to identify from the chaos the actors who appear most frequently in the story, who wield the most power, and who seem to hold sway over the narrative. If we can see that clearly, maybe we can push towards a better ending.

Sisyphus

Bureaucracies are enduring because they codify understanding of a system through regulation and daily practice.

One of the strangest things I encountered in government and civil society was a manual practice of estimation. Every week, a group would run an ancient desktop program that created a model of resource distribution. This model would be manipulated by two operators (one of whom we’ll come back to later) to create a “recommendation” for how these resources might be moved between locations. This model was then transmitted through a variety of systems, and eventually landed at the desk of a planner. The planner promptly threw it out, and proceeded to run their own model through a combination of automated and manual processes. These processes were then implemented and acted upon. One of the operators who I mentioned earlier, having realized their sisyphean task, had more or less given up. His colleague continued to diligently push the boulder uphill.

Sisyphus is a Greek legend of a cursed king forever pushing a boulder up a hill, only to have it roll down again. He is also patron saint of bureaucracies (at least to me). Nominally, he is being punished for his ways of subversion and deceit — breaking rules that were core to the Greek understanding of society. Bureaucracies are created to enforce and act along defined rulesets, and to enforce these rulesets, specific structures and systems calcify around them. These systems tend to follow rules themselves, each of which is specific to the organizations in question.

Playbook

You’re a young social entrepreneur with a head for technology and a desire to have impact. Unfortunately, you have just beamed into a confusing landscape of different agencies and organizations, interests and histories. Your mission is to figure out what is going on, and hopefully identify why your constituents are receiving such terrible services. However, you don’t know everything: after all, you have your experiences to work from and don’t really understand the experiences of those who have been working so long to deliver these services in the first place. You need to get to know the landscape before you can hope to change it.

Here’s a quick checklist of things to know BEFORE and DURING your use of these tools.

PRE-REQ

- Get introductions

- Know the ranks (eg. in US, GS scale and mil ranks)

- Know the acronyms (USTRANSCOM, FYSA, USCENTCOM, etc)

- Know the key players (commanders, public figures, major past projects)

Environmental Scan

- Go to whatever agency you’re in

- Get to know the stakeholders

- Find the highest level buy-in person you can: in DOD that was a combatant command general or a secretary

- Go to the place where the work happens

- Stay there for a while and just wander around talking to people and knocking on doors

Situational Awareness

- Map out the territory

- Who is everyone? Be specific. Write down names, job titles, what they do, who they report to, where they sit.

- Get security card access. ALWAYS.

- Get to know the security people.

- Get to know the people who do the work (low levels)

So once some of all of these are in place, now what?

Below are four tools that build on top of each other, and will give you some of the hard-to-get information you need to move forward and make decisions.

Archetypes — Identifying Roles

Who are these roles and what do they do? Why are they effective at their job and why are they not? What are their strengths, what are their weaknesses, and who do they depend on?

How long have they been there and where were they before?

Understanding the archetypes within the system allow us to break down the individual components of the system.

Working in government, the space I found most effective was in mapping out connections and “jobs.” Similar to a “jobs to be done” framework in product management, individuals in a bureaucratic organization tend to have very specific jobs and responsibilities. These responsibilities are then mapped across the hierarchy, and sometimes accomplished by delegation and management.

Why?

Articulating the archetypes you’ll encounter in your research gives you the basic knowledge to navigate a bureaucracy which often is self-replicating. It also forces you to narrow down the set of actors and look for commonalities across departments. Fundamentally, this is the building block of a number of clustering activities.

How To

Archetypes are an artifact that emerge out of research and exploration. Go into a team and start exploring. Ask yourself: who is doing the most talking? Who seems to be deferred to? Who is responsible for what? Who is mentioned the most in one-on-one interviews?

If you have a research team mate (I hope you do!), review your research notes and transcribe to post-it notes. From these notes, whittle the whole thing down to the worksheet provided below. Even if you didn’t get a chance to interview someone, try and fill out their role as much as possible.

Don’t fill in the Archetype name until last!

**EXAMPLE Names include: **The Trickster, The Explorer, The Caregiver, The Hero, The Rebel, The Artist, The Ruler. However, you should come up with your own archetype names. Sometimes “the Trickster” is actually a brilliant synthesizer of information, and works tirelessly to move the organization into a more progressive and effective direction. Perhaps they aren’t “The Trickster,” but “The Revolutionary” or “Hercules”, to return to the Greek theme.

When you are finished, you will have duplicate roles. This is fine, and you can simply enumerate them. A thing to keep in mind is that too many of one archetype may actually be part of the problem you’re trying to solve.

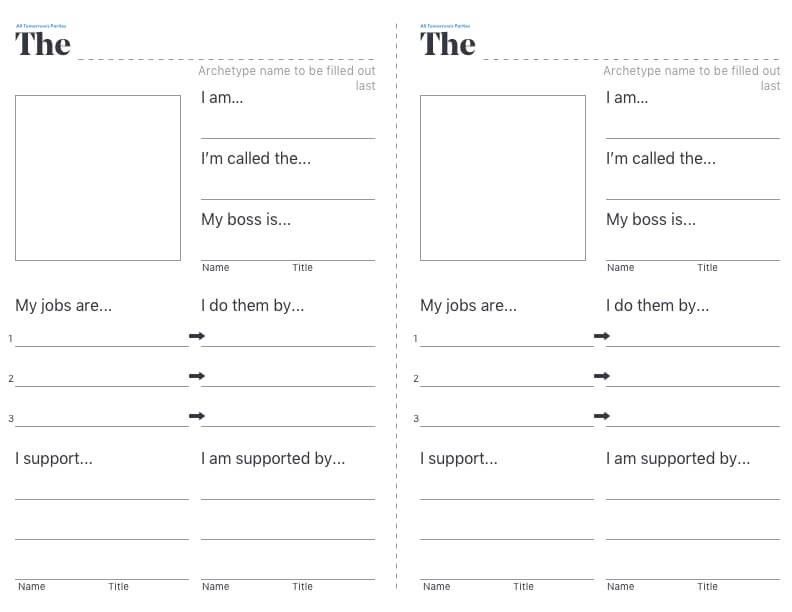

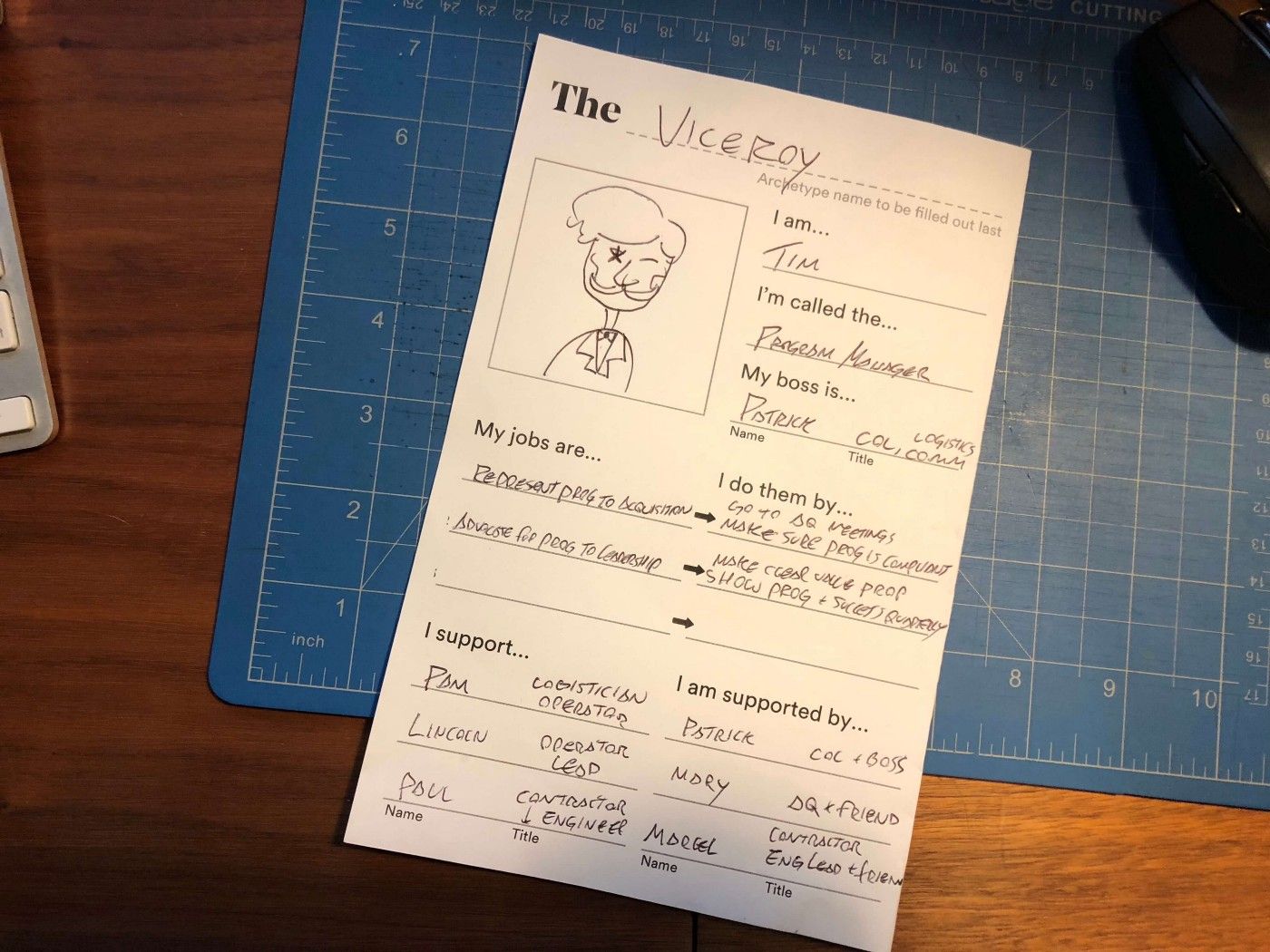

Worksheet

Example Scenario

Mapping the Pantheon (Mapping the Roles)

What is the story that creates the bureaucratic machine that we’re investigating? What is the myth that its operators believe? Its customers? How is that myth perpetuated, and who are the protagonists, the bit players, and the people sacrificed to the plot? The Pantheon as depicted on the Greek Parthenon and in friezes and artifacts across the ancient world, describes discussing the relationship between the different parts of a workflow or service. Its actors, its artifacts, and its outcomes. By visualizing, it gives us the basis to ask critical questions, and shift our understanding of the problem space

This activity requires you to embed with and map the existing system, and to extensively

Here, we map out a series of blueprints that map to the bureaucracies core functions, and weaving together the different stories that construct the system that you’re trying to intervene on.

Why?

The goal of this activity is to make this flow, failure points, and handoffs of a system obvious. We also need to be able to easily re-tell the story to the stakeholders involved. This tool pays dividends later on as well when re-designing a service, beyond our focus on stakeholder mapping in this group of tools.

How To

Print out a few of these sheets, and ask yourself: “Okay, what is the first step?”

In your notebook and during your interviews, you should have already started to map out some of these dynamics. Where does the information come from? Who owns that information? Who talks to the customer and who doesn’t? What is the catalyst for one of these workflows, and what causes the event or flow to be delayed?

These notes should be purposefully sketch-y. Don’t be afraid to cross out paths, make corrections, or work side-by-side with one of your government colleagues as you figure out what’s going out.

The path is important because it tells us where one smaller story starts, where it ends, and what new story starts where it left off. It helps us take a strategic lens to an information or human system, and trace it through its lifecycle. Finally, it surfaces the unknowns that are vital to making headway in this work.

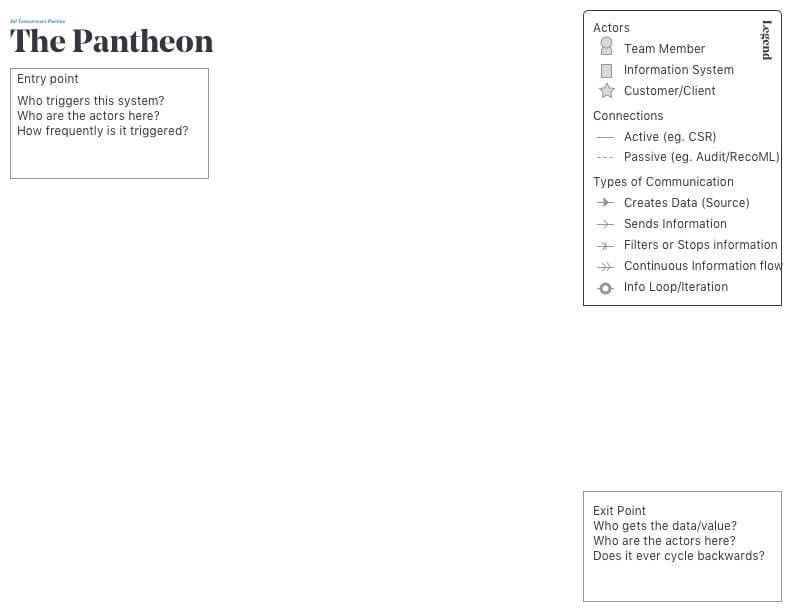

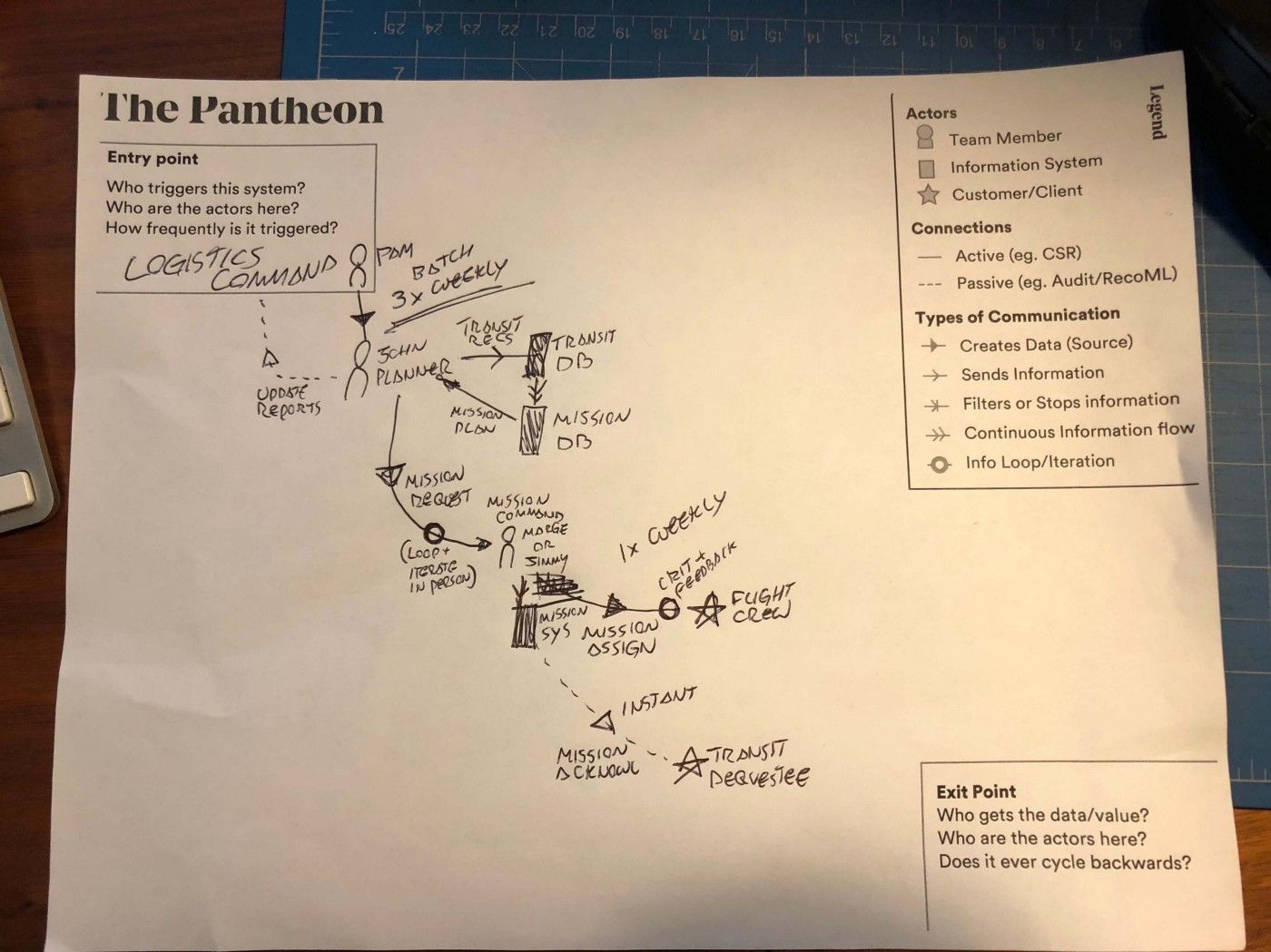

Worksheet

Example Scenario

Mapping the Actors (Figuring out your wedge)

Mapping the importance of characters within the ecosystem is a tool for the individual and for the team to prioritize characters within the narrative. Matthew Weaver, one of the early US Digital Service leads who went by “Rogue Leader” often said “There is no bottom” when referring to bureaucratic challenges. But if there’s no bottom, then at least we can focus on the space around us to try and affect change.

This activity is focused on looking at our cast of characters and our maps, and developing a sense of who is important. Who is on our core team, or our confidant? Who is in every meeting and has a stake, but isn’t that core trusted figure? Who needs to be kept in the know or appears from time to time, but doesn’t need to be apprised of everything, or might contribute very specific and narrow value? Who do you want to push out, or just inform on a need to know basis?

Why?

This framework is an excellent consensus building tool for your team, as well as a good way to communicate your understanding of the stakeholder map to the stakeholders themselves.

By asking these questions objectively and looking at the dynamics of who you want to bring closer and who you want to push out. You can push the question of “This person should be on the core team but wasn’t invited” towards “how do I get them closer?” or “Why not?”

How To

Start by going through each of the archetypes. In pen or pencil, draw a little caricature or symbol, and write their name and what they do along the graph. You can also write them on small post-it notes or stickers, to let you move people around.

Looking at the two axes on the graph, plot where they might be. This particular graph is intentionally biased towards importance to project vs. importance to bureaucracy when defining the different circles. If there are other biases or relationships that need to be captured, make sure you do that as well! As you draw out the different actors, always write down the REALITY of where they are, vs the IDEAL of where they might be. To represent that ideal, use arrows to communicate with your team where these folk should ideally be, and use that as a starting point to discuss how you might get them there.

Worksheet

Example Scenario

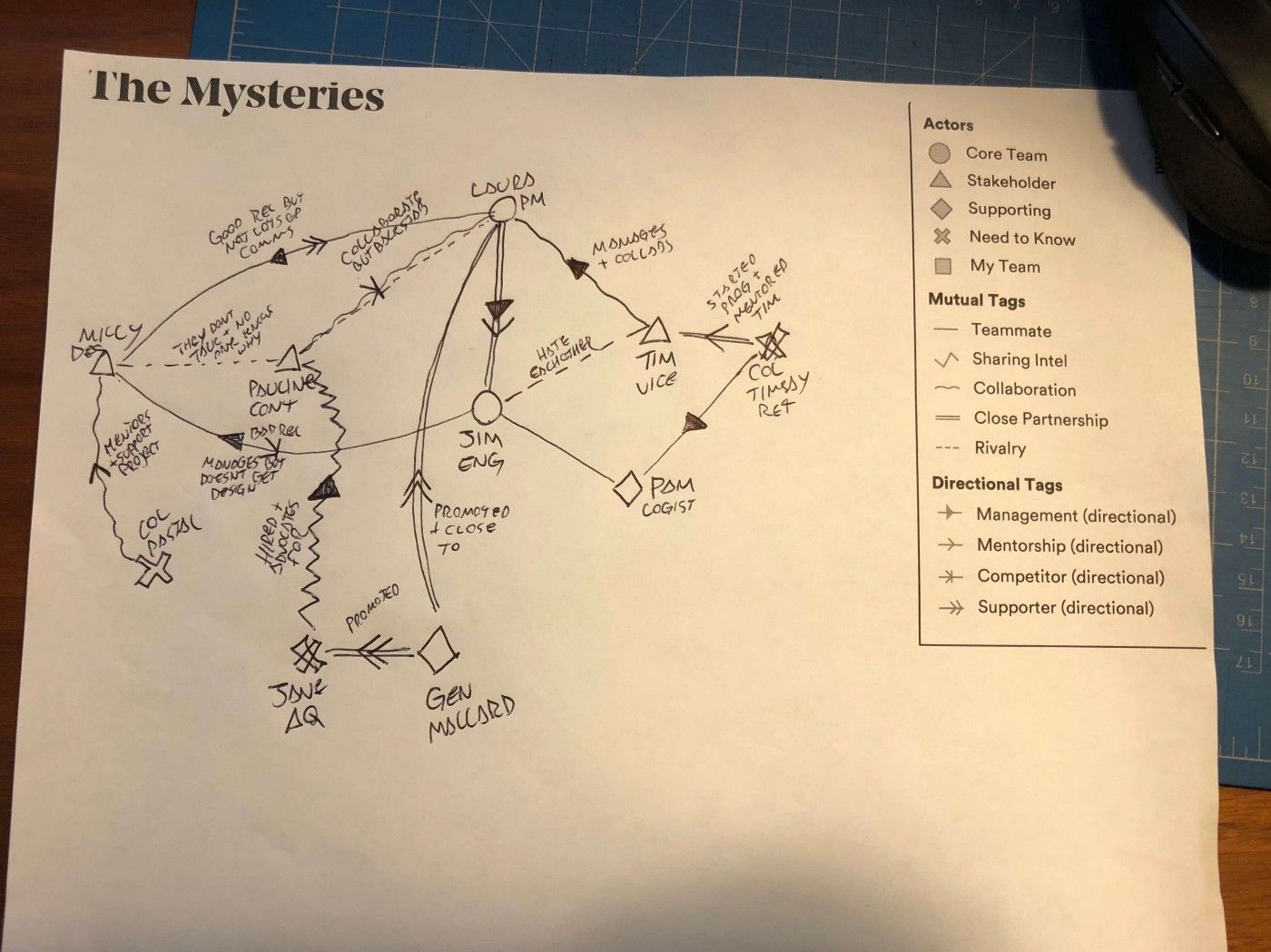

The Mysteries (Mapping the dark matter)

There’s the HIERARCHY of a bureaucracies and the SUBSTRUCTURE of the bureaucracy. The hierarchy exists above the surface and is often already mapped (or at least overt). The substructure exists below the surface and is non-obvious, but becomes intuitive to those who exist in that bureaucracy for long enough.

Consider the legend of Zeus and Dionysus. Dionysus is a translation of a hedonistic cult religion in the very early days of Greece. He’s the god of wine and alcohol, and also of madness. He doesn’t fit very well into the Pantheon, and yet is pervasive in Greek legends and tragedy. The Dionysian Mysteries were a set of practices that effectively undermined social constraints: a classical world version of basement concerts and beer pong. EVERY society has these things, as does every bureaucracy. They play the role of subverting the entrenched structure to really get things done. In this case, we want to understand WHO is a catalyst for this, WHERE these events occur, and WHY things have ended up this way. What are the stories behind the stories that make us need to break free?

In a research sprint I did at a hospital, I discovered that the real connectors were program admins: across deeply siloed research and technical units, the program admins were all only one or two steps removed from each other and always knew which other admin to connect with after about 6mo on the job. These admins became de-facto gatekeepers to the programs, despite not having substantive power or title, and ultimately the design work (building more densely networked and open programs) resolved around their needs and capacity.

Why?

This penultimate tool is meant to be a practical and evolving sketchpad throughout the program’s evolution. It should serve as a reference point within the team when making decisions about stakeholders and developing strategies for moving forward.

Also, and I apologize to our government friends, it’s also not always the best tool to share with your clients and government partners. This is a planning tool for the consultant team to make sense of an environment that everyone else takes for granted

How To

This is the last step, and is the raw material for a strategy to influence the program. I always start with the core team, and organizing around them. This is a very practitioner-centric approach and not always the right one, but it is often where I am the most engaged. From there, go through your list of archetypes and the folk that you’ve listed on the Mapping the Actors activity, and list them all out. Start to draw lines between them, one-by-one. Who is a close friend? Who collaborates? Sometimes you can have both: rivals who nonetheless share intel, or teammates who are also close competitors.

Indicate the directionality of relationships too. These can sometimes be bi-directional. I’ve seen situations where managers are managing those who see them as competitors, or mentors whose status has been uplifted by their mentees. If there are other types of relationships, fill them in and find a way to represent them.

This activity is best done in a team setting, where everyone can contribute their opinion and perspectives on the relationships.

Worksheet

Example Scenario

What’s next?

You’ve used these tools to try and get an understanding of this landscape. So what’s next? Hopefully, you should have a good understanding of who all the major players are, who you want to be involved where, and how you might move forward on having a positive impact.

Here’s a quick checklist that can get you going on asking the questions to have impact.

- Use these tools to sketch out current AND ideal states

- Bring sketches along so you can show people in future interviews (“is this right? does this make sense?”)

- Who do you want closer to the project? Who do you want pushes out?

- Use your understanding of the Mysteries and Dark Matter to figure out who you need to win over and convince to push the problematic people out

- Who do you need to get in a room in order to collaborate?

- Who do you need to kick out of the room because they force themselves in?

This enhanced knowledge will help you understand where your technology and where your skills as a social entrepreneur will have the greatest impact, and by bringing those who you’re hoping to work with along for the ride, hopefully you’ll have made some great allies along the way.

If you have any questions, contact me at alb@andrewlb.com and we can chat about how this approach might work for your specific challenge.

Originally published at pit.andrewlb.com on February 1, 2018.